Justin Favaro, MD, Ph.D., Oncology Specialists of Charlotte, PA

Immunotherapy is by no means new to the world of cancer treatment. In fact, it was first discovered in 1891 by Dr. William B. Coley, who injected killed bacteria into tumors and realized a reduction in the tumor size. Fast forward to 2019, and multiple Immunotherapy options are now available for patients.

Immunotherapy, according to the American Cancer Society, is a specialized treatment that uses a person’s immune system to attack cancer cells. As seen in Figure 1, tumor cells can turn off T cell activity by interacting through specific receptors. This allows tumor cells to evade the immune system and continue to grow. Drugs which block the T cell-tumor interaction, such as Keytruda as seen in Figure 3, allow the T cells to remain active and form an immune response against the tumor cells.

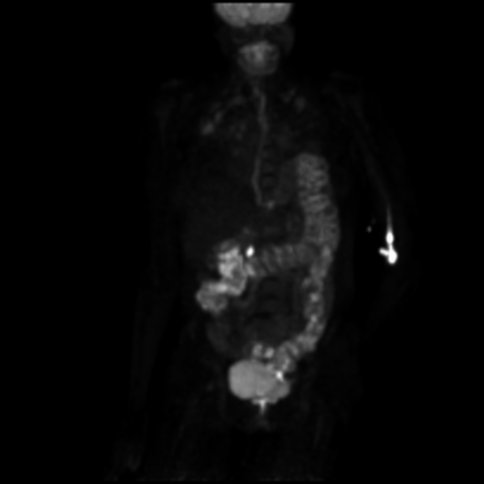

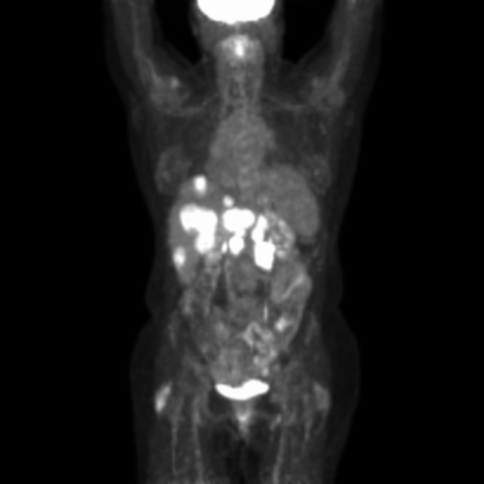

In 2017, I began treating a 52-year-old otherwise healthy female with stage IV high-grade neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. She presented with metastases to the liver, peripancreatic lymph nodes, and abdominal pain. I treated her with combination chemotherapy, and she had improvement of her abdominal pain but suffered the inevitable side effects of the treatment. After one year on different combinations of chemotherapy, her disease progressed with increasing pain and increasing size of the liver and peripancreatic metastases. We began treatment with dual agent immunotherapy, and after three treatments, she had a dramatic clinical benefit and reduction in the size of the metastases. See Figure 2. The patient had side effects of diarrhea and pneumonitis, which are controlled on steroids. Recently, she suffered a stroke and is currently off treatment, recovering well and remains in remission.

Many of us followed the story of former President Jimmy Carter, who in 2016, at the age of 91, was diagnosed with stage IV melanoma with metastases to the brain and liver. He was treated with immunotherapy and radiation therapy and has since led an active life. What a dramatic improvement in outcomes for this disease compared to just a few years ago.

Immunotherapy does not work for all patients. Tumors with the highest mutation burden (lung, melanoma, and bladder) have shown the best response rates, while colon, prostate, and others have a lower response rate. The amount of expression of PD-L1 receptor on the tumor surface and surrounding cells can predict the benefit of these drugs in some cases. The side effects are typically manageable with steroids, but rarely they can be more severe or fatal.

We are seeing more immunotherapies studied earlier in the course of the disease and combined with chemotherapy or targeted agents. With success seen in many highly mutated tumors, I am hopeful for continued improvements in outcomes for the patients with the less immunogenic tumors. The use of newer immunotherapy drugs alone or in combination with other treatments may eventually transform cancer into a chronic disease.

published: July 24, 2019, 8:49 a.m.